16 In-Class Assignment: Linear Dynamical Systems

Contents

16 In-Class Assignment: Linear Dynamical Systems#

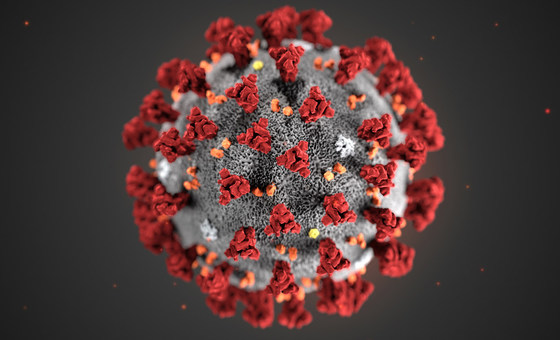

Image from: [https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/field/image/1583952355.1997.jpg)

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pylab as plt

import numpy as np

import sympy as sym

sym.init_printing()

1. Epidemic Dynamics - Discrete Model#

The dynamics of infection and the spread of an epidemic can be modeled as a linear dynamical system, specifically a Markov model.

We count the fraction of the population in the following four states:

Susceptible: the individuals can be infected next day

Infected: the infected individuals

Recovered (and immune): recovered individuals from the disease and will not be infected again

Deceased: the individuals died from the disease

We denote the fractions of the population in each these four states on day \(t\) in a state vector \(x_t \in \mathbb{R}^4\). For example \(x_t = [0.8,0.1,0.05,0.05]^T\) means that on day \(t\), \(80\%\) of the population are susceptible, \(10\%\) are infected, \(5\%\) are recovered and immune, and \(5\%\) are deceased.

We choose a simple model here. After each day,

5% of the susceptible individuals will get infected

95% of the susceptible individuals will not get infected, but remain susceptible

3% of infected inviduals will die

10% of infected inviduals will recover and be immune to the disease

4% of infected inviduals will recover but will not be immune to the disease

83% of the infected inviduals will remain infected

All recovered and immune individuals will remain recovered and immune

All deceased individuals will remain deceased

Then, if we know the fraction of the population in each of the four states on day \(t\), i.e., \(x_t\), we can compute the fraction of the population in each of the four states on day \(t+1\) (the next day) via the equation $\(x_{t+1} = Px_t\)\( where \)P\( is the \)4 \times 4\( state transition matrix whose \)(i,j)\(-th entry is the fraction of individuals in state \)j\( on day \)t\( who will be in state \)i\( on the next day. For this scenario, the matrix \)P\( is \)\(P = \begin{bmatrix} 0.95 & 0.04 & 0 & 0 \\ 0.05 & 0.83 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0.1 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0.03 & 0 & 1\end{bmatrix}.\)$

✅ Do this: Suppose we start with an initial state vector of \(x_0 = [1, 0, 0, 0]^T\) for day \(t = 0\), i.e., everyone is alive and susceptible to becoming infected. The for loop below calculates the fraction of the population in each of the four states on day \(t = 50\), i.e., \(x_{50}\) by repeatedly multiplying the current day’s state vector by the probability transition matrix \(P\) to get the next day’s state vector.

P = np.matrix([[0.95, 0.04, 0, 0],[0.05, 0.83, 0, 0],[0, 0.1, 1, 0],[0,0.03,0,1]])

x0 = np.matrix([[1],[0],[0],[0]])

x = x0

for t in range(50):

x = P*x

print(x)

If everything worked correctly, you should see that on day \(t = 50\), roughly \(15.04\%\) of the population is still susceptible to this infection, \(5.58\%\) of the population are infected, \(61.06\%\) of the population are recovered and immune, and \(18.32\%\) of the population are deceased.

We can also derive an explicit formula for the state vector on day \(t\) in terms of the state transition matrix \(P\) and the initial state vector \(x_0\). By repeatedly using the recursive relation \(x_{t+1} = Px_t\), we find that the state vector on day \(1\) is $\(x_1 = Px_0,\)\( the state vector on day \)2\( is \)\(x_2 = Px_1 = P(Px_0) = P^2x_0,\)\( the state vector on day \)3\( is \)\(x_3 = Px_2 = P(P^2x_0) = P^3x_0,\)\( the state vector on day \)4\( is \)\(x_4 = Px_3 = P(P^3x_0) = P^4x_0,\)\( and in general, the state vector on day \)t\( is \)\(x_t = P^tx_0.\)$

So to compute the state vector on day \(t\), we need to compute the matrix \(P\) raised to the \(t\)-th power. If \(t\) is large, multiplying \(P\) by itself \(t\) times can take a while. But as we previously learned, we can compute high powers of a matrix via diagonalization. Specifically, if the \(4 \times 4\) matrix \(P\) has \(4\) linearly independent eigenvectors, we can write \(P = VDV^{-1}\) where \(D\) is a diagonal matrix whose diagonal entries are the eigenvalues of \(P\) and \(V\) is a matrix whose columns are the eigenvectors of \(P\). Then, \(P^t = VD^tV^{-1}\) where \(D^t\) is simply a diagonal matrix whose entries are the eigenvalues of \(P\) raised to the \(t\)-th power. Hence, \(x_t = P^tx_0 = VD^tV^{-1}x_0\).

✅ Do this: In the cell below, first find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of \(P\). Then, use these to construct the matrices \(D\) and \(V\) to diagonalize \(P = VDV^{-1}\). Then, compute \(x_{50} = VD^{50}V^{-1}x_0\) and see if you get the same state vector as you did via the above for loop.

#Put your answer to the above question here

Now, let’s consider what happens to our population in the long-run, i.e., the limit of the state vector as \(t \to \infty\).

Since $\(x_t = P^tx_0 = VD^tV^{-1}x_0,\)\( the limit is \)\(\displaystyle\lim_{t \to \infty}x_t = \lim_{t \to \infty}VD^tV^{-1}x_0 = V\left(\lim_{t \to \infty}D^t\right)V^{-1}x_0.\)$

So to figure out the limit of our state vector as \(t \to \infty\), we need to figure out what happens to the matrix \(D^t\) as \(t \to \infty\).

✅ Do this: Write down the following:

the matrix \(D\) that you got when diagonalizing \(P\)

the result of raising \(D\) to the \(t\)-th power (this will depend on \(t\))

the limit of \(D^t\) as \(t \to \infty\) (think about what happens when \(t\) gets really big)

✅ Do this: In the cell below, compute the limit of the state vector \(\displaystyle\lim_{t \to \infty}x_t\) using the formula \(\displaystyle V\left(\lim_{t \to \infty}D^t\right)V^{-1}x_0\) along with the value of \(\displaystyle\lim_{t \to \infty}D^t\) that you calculated.

#Put your answer to the above question here

✅ Do this: Based on your calculation of \(\displaystyle\lim_{t \to \infty}x_t\) above, when this epidemic is over, what percentage of the population will have died and what percentage of the population survived?

Type your answer here.

✅ Do this: Let’s check that our state vector \(x_t\) does actually converge to the limit that we computed. Write code to compute \(x_t\) for \(t = 0,1,2,\ldots,200\) and plot each of the four components of \(x_t\) vs. \(t\), i.e., plot the fraction of the population that is in each of the four states over the first \(200\) days. You may compute the state vectors \(x_t\) either iteratively or via diagonalization, whichever you prefer.

Hint: You will likely want to store the state vectors \(x_0, x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_{200}\) as columns in a \(4 \times 201\) numpy array (or matrix), and then plot each row.

#Put your answer to the above question here

2. Epidemic Dynamics - Continuous Model#

Instead of using the discrete markov model, we can also use a continuous model with ordinary differential equations.

Let \(y_1(t)\), \(y_2(t)\), \(y_3(t)\), and \(y_4(t)\) denote the fraction of the population that is susceptible, infected, immune, and deceased respectively at time \(t\). Consider the following model:

with initial conditions \(y_1(0) = 1\) and \(y_2(0) = y_3(0) = y_4(0) = 0\), i.e., everyone is susceptible.

The equation for \(\dot{y}_1(t)\) models the fact that the fraction of the population that is susceptible \(y_1(t)\) decreases as susceptible people become infected, and it increases as infected people recover without becoming immune to the epidemic. You can come up with similar rationales for the other three equations.

We can write this system of differential equations in matrix form \(\dot{y}(t) = Ay(t)\), i.e.,

for some constants \(a_{i,j}\).

✅ Do this: Create the \(4 \times 4\) matrix \(A\) in Python below

# Put your answer to the above question here.

The solution to single variable ODE \(\dfrac{dy}{dt} = a y(t)\) with initial condition \(y(0) = y_0\) is given by \(y(t) = y_0e^{at}\). You can easily check that \(y(t) = y_0e^{at}\) is the solution since \(y(0) = y_0e^{a \cdot 0} = y_0\) and \(\dot{y}(t) = \dfrac{d}{dt}\left[y_0e^{at}\right] = ay_0e^{at} = ay(t)\).

Similarly, it can be shown that the solution to the \(n\)-variable ODE \(\dot{y}(t) = Ay(t)\) with initial condition \(y(0) = y_0\) is given by $\(y(t) = e^{tA}y_0\)\( where \)e^{tA}\( is the matrix exponential of \)tA$.

Recall that if \(A\) is an \(n \times n\) matrix, then the exponential of the matrix \(tA\) is the \(n \times n\) matrix defined by the series $\(e^{tA} = \dfrac{(tA)^0}{0!}+\dfrac{(tA)^1}{1!}+\dfrac{(tA)^2}{2!}+\cdots+\dfrac{(tA)^d}{d!}+\cdots\)$

If \(A\) has \(n\) linearly independent eigenvectors, (so that we can diagonalize \(A = CEC^{-1}\) where \(C\) is a matrix whose columns are the \(n\) linearly independent eigenvectors of \(A\), and \(E\) is a diagonal matrix with the eigenvalues \(\lambda_1,\ldots,\lambda_n\) on the diagonal), then for any real number \(t\), the matrix exponential of \(tA\) is $\(e^{tA} = Ce^{tE}C^{-1}\)\( where \)e^{tE}\( is a diagonal matrix with the numbers \)e^{\lambda_1 t}, e^{\lambda_2 t}, \ldots, e^{\lambda_n t}$ on the diagonal

✅ Do this: The code below computes the solution to the system of differential equations at \(t = 50\), i.e., \(y(50) = e^{50A}y_0\).

lam, C = np.linalg.eig(A)

Cinv = np.linalg.inv(C)

y0 = np.matrix([[1],[0],[0],[0]])

y50 = C*np.diag(np.exp(50*lam))*Cinv*y0

print(y50)

Note that this continuous model is not exactly the same as the discrete model. So it is expected that \(y(50) \neq x_{50}\). However, they should be similar.

✅ Do this: Make a plot of \(y_1(t)\), \(y_2(t)\), \(y_3(t)\), and \(y_4(t)\) vs. \(t\) over the range \(0 \le t \le 200\), and check that the plots look similar to that of the discrete model.

y0 = np.matrix([[1],[0],[0],[0]])

y_all = np.matrix(np.zeros((4,201)))

### Your code starts here ###

### Your code ends here ###

for i in range(4):

plt.plot(y_all[i].T)

If there’s still time left in class, consider what happens to our population in the long-run, i.e., \(\displaystyle\lim_{t \to \infty}y(t)\).

Since $\(y(t) = e^{tA}y_0 = Ce^{tE}C^{-1}y_0,\)\( the limit is \)\(\displaystyle\lim_{t \to \infty}y(t) = \lim_{t \to \infty}Ce^{tE}C^{-1}y_0 = C\left(\lim_{t \to \infty}e^{tE}\right)C^{-1}y_0.\)$

So to figure out what happens to our population in the long-run, we need to figure out what happens to the matrix \(e^{tE}\) as \(t \to \infty\).

✅ Do this: Write down the following:

the matrix \(E\) that you got when diagonalizing \(A\)

the matrix exponential \(e^{tE}\)

the limit of \(e^{tE}\) as \(t \to \infty\) (think about what happens when \(t\) gets really big)

✅ Do this: In the cell below, compute \(\displaystyle\lim_{t \to \infty}y(t)\) using the formula \(\displaystyle C\left(\lim_{t \to \infty}e^{tE}\right)C^{-1}y_0\) along with the value of \(\displaystyle\lim_{t \to \infty}e^{tE}\) that you calculated.

#Put your answer to the above question here

Written by Dr. Dirk Colbry and Dr. Santhosh Karnik, Michigan State University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.